Hey look! I’ve added audio. Kindly ignore the background hailstorm during the Virginia Woolf passage. It came up out of nowhere!

In this post:

• My own fangirling about FrizzLit and Footnotes & Tangents

• George Eliot fangirling about Sir Walter Scott

• ‘Hey, you, Cyclops! Idiot!’

• A Rumpelstiltskin rabbit trail

I know the month isn’t over quite yet, but I’m unlikely to start anything new in the next few days. Oh wait, that’s totally incorrect! I’ll absolutely be starting one or more new books between now (Friday, when I began writing this post) and next Tuesday. Incredible brain blip right there.

Because (fanfare)…earlier this week my Brave Writer editor gave me the booklist for the Dart literature guides I’ll be writing for the upcoming academic year’s slate. Nine middle-grade novels whose titles won’t be announced until the end of May, so I can’t share them yet. But it’s a delightful list. I’ll spend May reading all of them (or rereading, in a few cases) and choosing passages to write about. And generally mapping out my topics and writing plan for all nine issues. I’ll be writing one issue a month from June through next February (with possibly a tenth issue slipped in there somewhere).

The nice thing about having a dedicated reading month for my Dart work is that I can really immerse in the books, getting to know them all inside and out before I start writing about them. I like to supplement the print readings (pencil in hand, marking them up like crazy) with audiobook listens. Often, different qualities jump out at you when you’re listening. Plus I can garden while tuning into an audiobook: win/win.

Last year’s house move ate up my May reading month, so it feels extra-delicious this year. Time and a garden: that’s really all my little reading heart desires.

But back to April.

I continue to read like an English major—or like a Charlotte Mason-inspired homeschooler, which of course I am: multiple long, slow, gradual reads in progress for myself, and three more going with Huck and Rilla. It sounds mad, but it isn’t. In fact, it’s strangely restful. When you’re pacing out a novel over months or even a year (in the case of War and Peace), no single day’s allotment feels overwhelming. In fact, my biggest challenge has been not reading ahead.

Middlemarch

Dorothea was aware of the sting, but it did not hurt her. “No,” she said, “I still think that the greater part of the world is mistaken about many things. Surely one may be sane and yet think so, since the greater part of the world has often had to come round from its opinion.”

We’re in (I think) Week 14 of the

Book Club. I’m so in love with this class. So much meat! And spice! And merriment. In a recent session, I had the fun of presenting a George Eliot-Sir Walter Scott rabbit trail to the rest of the group. I’ll share it here, too, at the end of this post.Wolf Hall

This was a big week for the

Cromwell readalong gang! We finished the first book in Hilary Mantel’s trilogy. Listen, if you’re looking for something to nourish and exhilarate you for the rest of the year, you can’t do better than jump into one of ’s readalongs. If you subscribe to his Substack (free or paid), you’ll have access to all the previous posts. Simon’s weekly commentary is exceptionally good.He also writes a special post each week for paid subscribers, exploring the motif of ghosts and phantoms in the trilogy, and is currently offering 25% off paid subs.

War and Peace

Simon’s other year-long slow-read series is War and Peace. I’m captivated. I’ve taken to beginning my days with this one: I read the day’s chapter (usually quite short, perhaps ten or twelve minutes of reading) and then, a little later in the day, over breakfast usually, I open Substack Notes to read the chapter’s chat thread. This week I got swept up in Natasha’s excitement over her first ball and had to read ahead—and ahead some more.

A Writer’s Diary

All of this literary richness put me in the mood to spend a little time in Virginia Woolf’s diary. I’ve started it many times and have never read the whole book; but even a taste here and there does me good.

What sort of diary should I like mine to be? Something loose knit and yet not slovenly, so elastic that it will embrace any thing, solemn, slight or beautiful that comes into my mind. I should like it to resemble some deep old desk, or capacious hold-all, in which one flings a mass of odds and ends without looking them through. I should like to come back, after a year or two, and find that the collection had sorted itself and refined itself and coalesced, as such deposits so mysteriously do, into a mould, transparent enough to reflect the light of our life, and yet steady, tranquil compounds with the aloofness of a work of art.

The Odyssey

The kids and I continue to delight in Emily Wilson’s translation. Our pace is roughly one book (a chapter, essentially) a week, divided over several days. I’m reading it aloud and have to stop often for laughter and discussion. We spent last week in the Cyclops’ cave, and after Odysseus’s clever escape, his braggadocio—taunting the giant when his ship wasn’t yet out of boulder-tossing range—elicited a lot of amused exasperation from my teens.

‘Hey, you, Cyclops! Idiot!

The crew trapped in your cave did not belong

to some poor weakling. Well, you had it coming!

You had no shame at eating your own guests!

So Zeus and other gods have paid you back.’

My taunting made him angrier. He ripped

a rock out of the hill and hurled it at us.

It landed right in front of our dark prow,

and almost crushed the tip of the steering oar.

The stone sank in the water; waves surged up.

The backflow all at once propelled the ship

landwards; the swollen water pushed us with it.

I grabbed a big long pole, and shoved us off.

I told my men, ‘Row fast, to save your lives!’

and gestured with my head to make them hurry.(Book 9, “A Pirate in a Shepherd’s Cave”)

As Huck said: Dude!

Nineteeth-century fanfic

I also read some nonfiction this month, but this post is getting long, so I think I’ll jump to my Walter Scott story.

Chapter 57 of Middlemarch begins with an epigraph by George Eliot about discovering the fiction of Sir Walter Scott.

They numbered scarce eight summers when a name

Rose on their souls and stirred such motions there

As thrill the buds and shape their hidden frame

At penetration of the quickening air:

His name who told of loyal Evan Dhu,

Of quaint Bradwardine, and Vich Ian Vor,

Making the little world their childhood knew

Large with a land of mountain lake and scaur,

And larger yet with wonder, love, belief

Toward Walter Scott who living far away

Sent them this wealth of joy and noble grief.

The book and they must part, but day by day,

In lines that thwart like portly spiders ran

They wrote the tale, from Tully Veolan.

The “we” of this sonnet is believed to be Eliot—that is, Mary Ann Evans—herself. When George Eliot died, her friend and passionate admirer Edith Simcox wrote an obituary that included a story about Mary Ann’s first encounter with a Sir Walter Scott novel. As the story goes: when Mary Ann was a little girl, a neighbor loaned her big sister a copy of Scott’s Waverley. Mary Ann, who would have been about eight years old at this point, started reading it. But the book was returned before she finished. She was desperate to know what happened next in the story—so she started writing it herself, picking up at the part where she’d left off reading, when the hero has just gotten to Tully Veolan.

She writes and writes and writes, spinning out the tale in her spidery childish handwriting. Eventually the grownups find out and someone borrows the book back so she can finish reading it.

It tickles me to think that George Eliot got her start writing Walter Scott fanfic!

She remained a fan her whole life. There are several other Walter Scott references in Middlemarch. The chapter headed by the Waverley sonnet includes a hilarious scene in which Mary Garth’s brother reads Ivanhoe out loud to the family—a scene which will absolutely ring true to many of my fellow homeschoolers.

Jim was in the great archery scene at the tournament, but suffered much interruption from Ben, who had fetched his own old bow and arrows, and was making himself dreadfully disagreeable, Letty thought, by begging all present to observe his random shots, which no one wished to do except Brownie, the active-minded but probably shallow mongrel, while the grizzled Newfoundland lying in the sun looked on with the dull-eyed neutrality of extreme old age. Letty herself, showing as to her mouth and pinafore some slight signs that she had been assisting at the gathering of the cherries which stood in a coral-heap on the tea-table, was now seated on the grass, listening open-eyed to the reading.

Kid pestering his sister with a bow and arrows during a family read-aloud, check. Sleepy old dog, check. Kid covered in cherry juice, check.

Much earlier in the book, there’s a scene in the Vincy family’s drawing room in which Rosamund Vincy and her hapless suitor, Ned Plymdale, are looking together at a copy of Keepsake, “the gorgeous watered-silk publication which marked modern progress at that time.” Rosamund is more interested in flirting with the handsome young Doctor Lydgate, a newish arrival to the town of Middlemarch. Lydgate, to Ned’s annoyance, is totally snarky about Keepsake. He makes a crack that he wonders “which would turn out to be the silliest—the engravings or the writing.”

Well, it turns out that this scene is referring to a specific issue of Keepsake—the 1829 edition.

It just so happens that one year earlier, in 1828, Sir Walter Scott was offered the editorship of Keepsake. He wrote a diary entry about it that was quoted in a biography that Eliot happened be re-reading around the time she was writing Middlemarch.

Scott wrote that he had declined the offer, because “to become the stipendiary editor of a New-Year's-Gift Book is not to be thought of.” (Speaking of snark!) But to soften the blow he promised to write “some trifling thing or other” for an upcoming issue.

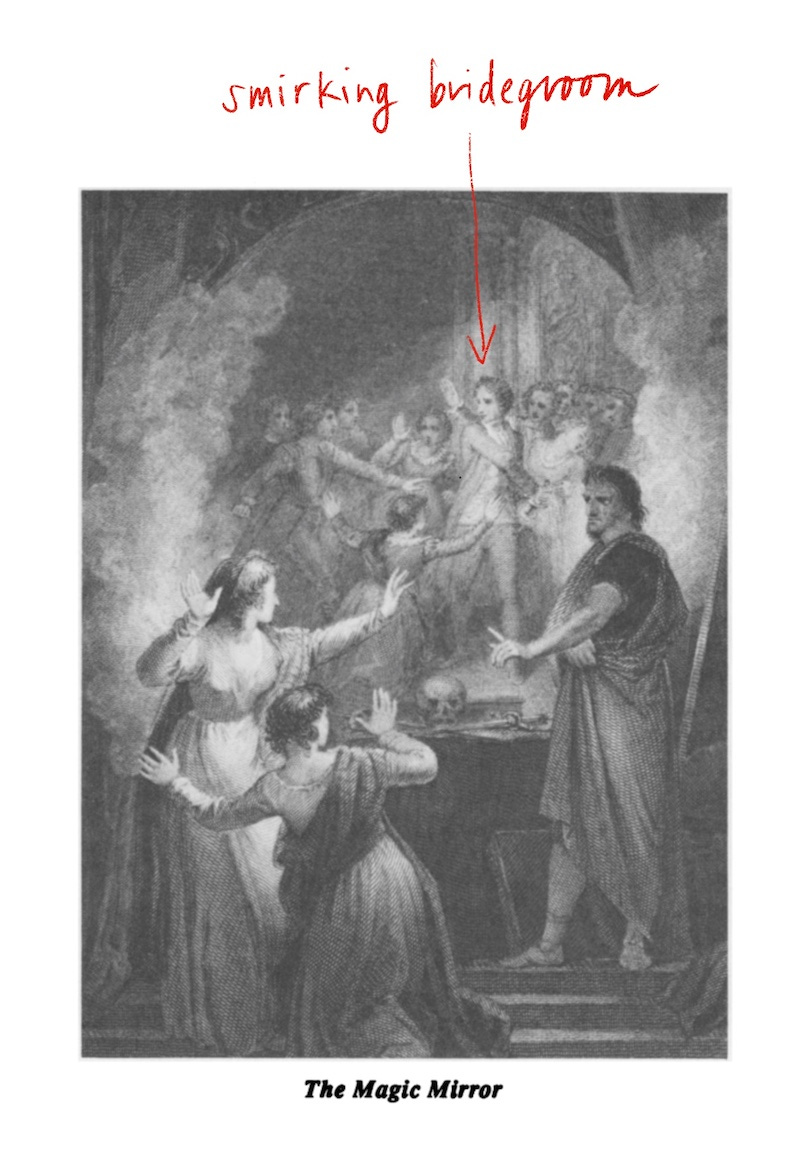

And that “trifling thing” was a story called “My Aunt Margaret’s Mirror,” which appeared in the 1829 edition—the very story Lydgate is snickering about. He mocks its illustration:

“Do look at this bridegroom coming out of church: did you ever see such a ‘sugared invention’—as the Elizabethans used to say? Did any haberdasher ever look so smirking?”

Rosamund is amused, but poor Ned is offended.

“There are a great many celebrated people writing in the ‘Keepsake,’ at all events,” he said, in a tone at once piqued and timid. “This is the first time I have heard it called silly.”

Well, he’s not wrong about the celebrated writers. Also in that issue of Keepsake were pieces by Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Mary Shelley.

Those triflers!

Delicious tale

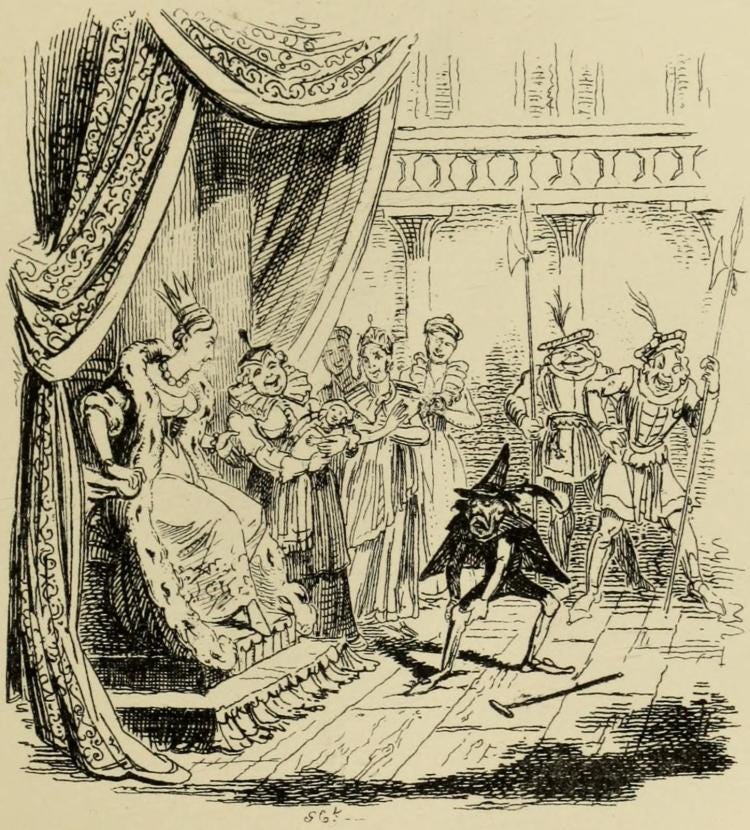

One of this week’s Middlemarch chapters has sent me on yet another rabbit trail: tracking down the “red volume” of fairy tales mentioned in the New Year’s chapter. Mary Garth is telling the “delicious tale” of Rumpelstiltskin to the younger Vincy children, a story she knows by heart because her little sister Letty (she of the cherry-stained face above) “was never tired of communicating it to her ignorant elders from a favorite red volume.”

Scholars have identified the book as the 1823 edition of German Popular Stories by the Brothers Grimm, translated by Edgar Taylor. Rumpelstiltskin is the final tale in the collection. An 1868 reprinting included an introduction by John Ruskin and a letter written to Taylor by—here he is again—Sir Walter Scott. He keeps popping up wherever I look!

It appears that George Eliot read the 1823 edition as a child. She would have been about four years old when it was published—probably around the same age as little Louisa Vincy, who, after listening wide-eyed to Mary Garth tell the story, runs to her mother, crying: “Oh mamma, mamma, the little man stamped so hard on the floor he couldn’t get his leg out again!”

How about you? Any standout books / quotes / rabbit trails for you this month?

I am reading The Illiad and The Odyssey later this year or early next. Using the Fagles translations but I have heard great things about the Wilson version. May have to read them twice!