Two well-dressed women and Peter Twist

The role of "respectful imagination" in Tolstoy's work...and my own

Long ago, the Laura Ingalls Wilder estate commissioned me to write two series of original novels, one about Laura’s maternal grandmother, Charlotte Tucker, and one about Charlotte’s mother, Laura’s great-grandmother, Martha Morse. There are lots of stories I could tell about writing those books—many of them chronicled on my blog, back in the day—but the one that came to me this morning was the story of some orchard robbers in Roxbury, Massachusetts, around 1817.

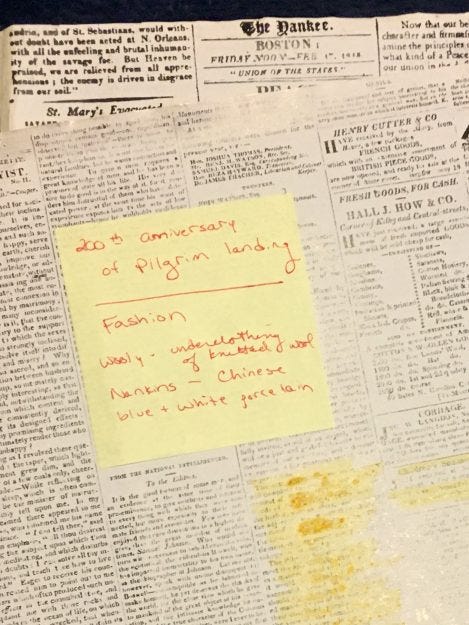

An article in The Yankee, a Boston-area paper, reported the arrest of “two well-dressed women and Peter Twist” in a Roxbury farmer’s apple orchard at midnight. This description both intrigued and delighted me. What was the story there? Why were the women unnamed? Why were they wearing their good clothes? What was the scope of the heist? Were they locals or just passing through, helping themselves as they went?

The article’s details were scanty, but I flagged it as a story I might want to use in one of the Charlotte books. Since I knew exactly when and where the real Charlotte had lived as a child, I scoured the Yankee and other papers for historical detail. Like the hurricane in On Tide Mill Lane: the local news told me whose roof was torn off and what other damages Roxbury folks suffered. There was the Brighton Cattle Show, right down to all the winners. The vandalism of a Bible in a Roxbury church. The first gaslights in Boston. The first elephant brought to North America.

“Respectful imagination”

This has always been my approach to historical fiction: imagining the stories behind the snippets of text in the historical record. For example, The Nerviest Girl in the World was sparked by the enchanting discovery of an incensed editorial in a 1911 San Diego County paper about how a troupe of cowboy actors was making the streets of La Mesa unfit for young girls. Why, these scoundrels said words like “Shucks” and “Darn” right out loud.1 For me, that article was love at first sight. I had to know more about these foulmouthed actors. The closer I looked, the more gaps I yearned to fill in. There had been a silent film studio in my town? That rabbit trail led me to the Perils of Pauline, and bit by bit a story—entirely fiction, but ignited by fact—came into focus.

The novelist Gail Godwin, in her book Father Melancholy’s Daughter, calls this the act of respectful imagination. To write fiction based on a historical event or figure, you learn as much as you possibly can from primary source material, and then—you craft a narrative that respectfully imagines what folks said, how things looked, what might have sparked an event that shows up only as a line in a newspaper article or an account book.

Tolstoy: the master of respectful imagination

I thought of Peter Twist and his fashionable but faceless female companions while reading yesterday’s daily chapter of War & Peace for the

readalong, brilliantly hosted by . The narrative describes an 1812 event that occurred as the French army approached Moscow, a conversation between Napoleon and a captured Cossack. Tolstoy rather wryly references an account of this event by the historian Adolphe Thiers, kicking it off with the observation that Thiers “is as right as other historians who look for the explanation of historic events in the will of one man…”2Which is to say: not all that right.

All through the book, Tolstoy has been laying out his conviction that the causes of historical events are never as easily boiled down as their chroniclers often suggest. History is not a linear series of dominoes, each tile neatly toppling the next one in the line: it’s a complex interweaving of thousands of small moments and fleeting choices. The cloth is woven from millions of gossamer threads.

And Tolstoy’s interest as a storyteller, it seems to me, as a first-time reader, is in closely observing a few of these threads, noticing how they contribute to the pattern. A letter, a dance, a heartbreak, a plume of cannon smoke, an awkward remark. A cornered she-wolf. A handful of stolen green plums. A lofty sky, a brooding old tree. And most of all, the innumerable human lives, each one a fiber that on closer inspection turns out to be its own vast tapestry of happenings, impressions, decisions, and passivities. Tolstoy takes us closer, closer, deeper into the weave—and each close-up reveals a whole world.

To switch metaphors: as I read him, I can’t help thinking of Horton Hears a Who: the mote of dust that contains a planet.

“Every face I look at seems beautiful to me”

He’s so in love with the world, Tolstoy is. For him the act of respectful imagination seems both a celebration and a sacrament. Thiers writes about a nameless Cossack captured by a French officer and trotted before Napoleon, whom the fellow is too oafish to recognize:

“The Cossack, not knowing in what company he was…talked with extreme familiarity of the incidents of the war.”3

Tolstoy gives—indeed, has already given—this man a name, a backstory, a personality. By this point in the book, we’ve had several encounters with the fellow.

“In reality Lavrushka having got drunk the day before and left his master dinnerless, had been whipped and sent to the village in quest of chickens, where he engaged in looting till the French took him prisoner. Lavrushka was one of those coarse, bare-faced lackeys who have seen all sorts of things, consider it necessary to do everything in a mean and cunning way, are ready to render any sort of service to their master, and are keen at guessing their master’s baser impulses, especially those prompted by vanity and pettiness.

Finding himself in the company of Napoleon, whose identity he had easily and surely recognized, Lavrushka was not in the least abashed but merely did his utmost to gain his new master’s favour.

He knew very well that this was Napoleon, but Napoleon’s presence could no more intimidate him than Rostov’s, or a sergeant-major’s with the rods, would have done, for he had nothing that either the sergeant-major or Napoleon could deprive him of.

So he rattled on, telling all the gossip he had heard among the orderlies. Much of it was true.”

“Respectful imagination” means seeing people in all their complexities and contradictions. And, as storyteller, loving them, warts and all.

I’ll never forget reading, in college, Betty Edwards’s Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, and how one of her students said that after taking Betty’s drawing class and working on portraits, every face she looked at seemed beautiful to her. The drawing lessons taught her to really look at people, and when she did, she saw beauty everywhere. In wrinkles, in noses and earlobes broadened with age, in freckles and eyelashes and glints of humor or grief.

I never did imagine the story of the orchard thieves into one of my Charlotte novels. But I used that newspaper clipping in several writing workshops over the years—some for kids, some for adults—handing out copies of the article and giving time for the participants to freewrite their version of the story behind those bald facts. Reading these stories, and sometimes writing my own alongside my students, I fell in love over and over. Felicity and Sarah, who were really very hungry. A band of wanderers, lost in the dark. Mrs. Minerva Twist and her sister, Nora Gumphrey, who secretly hated her brother-in-law, Peter, for getting them into this mess. Grass stains on the good linen shirtwaist. The smell of apples on the midnight air.

That’s why the language in Deadwood was so blisteringly profane. If the show had used the actual swear words of the time, the dialogue would have sounded laughably quaint to modern ears.

Maude translation, Book Three, Part Two, Chapter 7

Maude translation, footnote on page 762

huh. I'd always assumed that words like "shucks" and "darn" were just literary stand-ins for the actual words people were saying.

Love this idea of respectful imagination and how you apply it to Tolstoy's writing. And love this meditation on Lavrushka.